Postwar Kalamaria

Water supply

For many decades after the refugees’ arrival, the Greek state lacked the financial ability to provide the community with integrated infrastructure networks (water supply, sewerage, electricity, and paved roads). Finally, in the 1950s, the authorities embarked on the first real projects to improve the refugees’ daily lives. The only exception was the water supply network. In 1912 the municipal authorities commissioned the Belgian-funded Compagnie Ottomane des Eaux de Salonique to construct storage tanks in Evangelistria to supply Exohi.

The network limitations first manifested with the arrival of refugees in Kalamaria in 1922. The increased need for water led to a rotating water supply system with public shared taps that provided water for a few hours each day. In the 1930s, water was still scarce. The so-called “Havouza” was a storage tank built near the “Aristotelis” Orphanage to provide the adjacent settlement with water. In summer, the authorities were often forced to cut off the water supply for one or many days without any warning.

The water in the fountains came from Chortiatis. Several fountains were scattered in the settlements to serve the inhabitants’ multiple needs. Their primary function was to supply water when no house had a private water supply. At a distance of two hundred or three hundred metres, the communal fountains satisfied a basic need and functioned as meeting points for the refugees, who could exchange news and learn the latest gossip. Of course, all this was contingent on the absence of rain because mud made the fountains inaccessible. Among the essential touloumpes (fountains) was the one near the salted fish factory in Karabournaki, the fountain at the corner of Chilis and Poulantzaki streets in the centre of Kalamaria and the public fountain on Kallidou street.

In 1939, a pumping station was built in Katirli to supply the centre of Kalamaria and the surrounding settlements with water from springs in Chortiatis and the aqueduct of the Charilaou settlement. A pumping station had been built earlier in Nea Krini to supply the community and Aretsou. At the same time, the authorities carried out drilling in Aretsou, Mikra and the settlement of Ktinotrofikon next to the Aristotelis Foundation.

Towards the end of the 1950s, the rotating water supply system and the communal fountains began to be phased out. Indoor plumbing replaced them. The transition from the old to the new water supply system was slow because each family paid separately what was due for the private water supply. In 1969 the newly established Thessaloniki Water Supply Organisation constructed the large capacity tank in Koimitiria. Kalamaria would henceforth be supplied with water from Kalochori through the pumping station on Kassandrou Street.

Sewage disposal

In the early years, Kalamaria did not have a comprehensive sewerage system. As a result, residents were forced to use cesspools and shared toilets, which had been installed by the companies that built the settlements (one watertight septic tank per building block). A municipal car emptied the tanks and discharged the sewage into streams near Neo Rysio. Since many houses and shacks had individual septic tanks, there were also workers who dug new holes in the yard and used a bucket to transfer the excrement from the septic tank that was full to the new one.

In the 1960s, there was a sewage network in Kalamaria, Aretsou, Nea Krini and Finikas. The network used collector ducts to direct sewage into the sea. Where sewers were lacking, residents collected sewage in private septic tanks while rainwater flowed into the sea from the streets. In the same decade, two small biological treatment plants operated in Finikas and Nea Krini to serve the newly built workers’ apartment buildings.

In 1976, the construction of central sewerage pipelines began, which led the wastewater to the sea without treatment. The sewage was not significant because Kalamaria was relatively sparsely populated, and the houses were predominantly single-storey. As the population grew, the problem of wastewater management worsened, but the presence of biological treatment plants in Finikas and Nea Krini had already paved the way for a modern waste management service based on the collection, treatment and utilisation of the final products without endangering the environment.

Electrification

The “Pollatos and Bros Electric Company of the Suburbs of Thessaloniki” factory started operating in Kalamaria in 1932. Its headquarters were located at the intersection of Pontou and Aigaiou streets. The increased price of the supplied electricity prevented residents from becoming customers and limited the electric lighting to a handful of streets illuminated for a few hours. Moreover, the unbearable terms of the contract with the company caused an outcry: “Let the owners of the brightly lit mansions, who appear as our saviours, come and sit in our dark houses. The right honourable mansion owners should not forget that we survive on primitive means. If they pay 4.85 per kilowatt, we pay 15-20 drachmas for oil.” For several more years, the price remained high, and streets were lit mainly with oil and gas lamps.

In June 1944, the dredgers Axios and Strymon docked in Thessaloniki to supply electricity. Unfortunately, the State Operation of Tramways and Electric Lighting of Thessaloniki could not meet the city’s needs. Therefore, the ship’s crews became temporary employees of the power company. At the same time, the dredger Achinos anchored permanently in front of the Allatini flour mill to assist in the electrification of Kalamaria.

From 1946 to 1957, the electricity supply was provided by the “Petichaki and Co. Electricity Lighting Company of Thessaloniki”, which was finally acquired by DEI (Public Power Corporation), which was founded in August 1950 “for the public interest”.

Public transportation

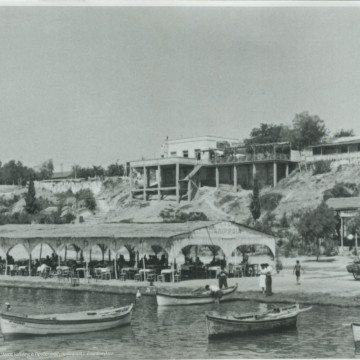

The connection of Kalamaria with Thessaloniki was a critical and chronic problem. According to the testimony of an old resident, “the people of Kalamaria were forced to walk to the Depot, whether it snowed or rained with frozen hands, hungry, unhappy, and poorly dressed. In Depot, they got on the tram if they could afford the fare or else they went on foot down to Egnatia.” However, those who lived near the beach could use the small boats, which sailed from the docks in Kouri and Nea Krini to Thessaloniki from 1932 until the late 1960s.

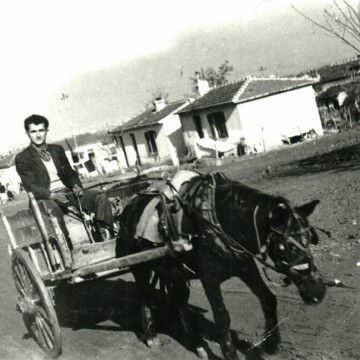

The residents’ main demands were the extension of the tram to Kalamaria and a ticket price reduction, but the proposals were never implemented. Even moving around within the municipal boundaries of Kalamaria could turn into a small odyssey. You could quickly lose your shoes in the mud that covered everything with the slightest rainfall. These conditions gave Kalamaria and its inhabitants the nickname “tsamuria” (mud in Pontic Greek). The systematic surfacing of roads with asphalt concrete began in the early 1960s.

In the interwar period, a trip to Thessaloniki required various means. The people of Kalamaria could take buses to the Depot and then board the tram to complete their journey. After the departure of the Germans, direct bus lines connecting Kalamaria with Thessaloniki gradually began to be established. In 1950 there were four bus lines from Tsimiski Street to the settlements of Votsis, Karabournaki, Aretsou, Nea Krini and downtown Kalamaria. In the 1960s, the buses started from Venizelou Street and headed to Karabournaki, Nea Krini, Finikas, Agios Panteleimonas, Votsis and the centre of Kalamaria.

The conditions on the buses were poor. Passengers had to deal with overcrowding and quarrels at bus stops and onboard the vehicles. The service was infrequent and lacked safety features or basic amenities. The residents of Thessaloniki who wished to visit the beaches of Kalamaria were more fortunate because they could use steamboats from the White Tower docks. These boats entered regular service in 1951 and operated for two decades.